Social vulnerability and parental role in four settings, Medellín, Colombia

Vulnerabilidad social y rol parental en cuatro escenarios, Medellín, Colombia

Luisa Betancur *  Mariana Arango

Mariana Arango  , Nagibet Casas

, Nagibet Casas  , Sebastián Velásquez

, Sebastián Velásquez  , Abad Parada

, Abad Parada  and Alexandra González

and Alexandra González

* Tecnológico de Antioquia Institución Universitaria, Colombia – Correo: luisa.betancur22@correo.tdea.edu.co – ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1007-5191

How to cite this article: Betancur, L., Arango, M., Casas, N., Velásquez, S., Parada, A. y González, A. (2024). Social vulnerability and parental role in four scenarios, Medellín, Colombia. Jangwa Pana, 23(1), 1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.21676/16574923.5003

Received: 13 /01/2023

Approved: 04/12/2023

Published: 01/01/2024

Editor’s note: This article has been translated into English by Express, with funding from the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (Minciencias) of Colombia.

Research article / Artículo de investigación

Abstract

Social vulnerability is a problem to which many families are exposed: domestic violence, drug addiction, deprivation of liberty, economic precariousness or little access to health and education services. Social vulnerability influences family dynamics, upbringing and the formation of healthy affective bonds. The aim of this article was to understand the relationships between social vulnerability and parental role from the analysis of data collected in four different contexts. The research was framed in the qualitative approach, the interpretive paradigm and the phenomenological method. The participants corresponded to eight intentionally selected individuals in four contexts in the city of Medellín in Colombia: the Unbound Foundation, the La Paz Penitentiary Center, the Secretary of Health and Social Protection of the Itagüí Mayor’s Office and the Pueblo de los Niños Corporation.The semi-structured interview related to the categories social vulnerability, parental role and parental skills was used as a data collection technique. The results show that the parental role and family dynamics -relationship, affective ties and communication- can be affected by different economic and social factors that affect social vulnerability. It is concluded that the fathers and mothers of families that are in situations of vulnerability face various obstacles that prevent them from exercising their parenting in an optimal way, since opportunities play a fundamental role for the creation and execution of a family life project.

Keywords: Social Vulnerability; Parental Role; Family; Vulnerability contexts.

Resumen

La vulnerabilidad social es una problemática a la que muchas familias están expuestas: violencia intrafamiliar, drogodependencia, privación de la libertad, precariedad económica o escaso acceso a servicios de salud y educación. La vulnerabilidad social influye en las dinámicas familiares, la crianza y la formación de lazos afectivos sanos. Este artículo tuvo como objetivo comprender las relaciones entre vulnerabilidad social y rol parental desde el análisis de información recolectada en cuatro contextos diferentes. La investigación estuvo enmarcada en el enfoque cualitativo, el paradigma interpretativo y el método fenomenológico. Los participantes correspondieron a doce individuos seleccionados de manera intencionada en cuatro contextos de la ciudad de Medellín en Colombia: la Fundación Unbound, el Centro Penitenciario La Paz, la Secretaría de Salud y Protección Social de la Alcaldía de Itagüí y la Corporación Pueblo de los Niños. Se empleó como técnica de recolección de datos la entrevista semiestructurada relacionada con las categorías vulnerabilidad social, rol parental y competencias parentales. Los resultados muestran que el rol parental y la dinámica familiar —relacionamiento, lazos afectivos y comunicación— pueden verse afectados por distintos factores económicos y sociales que inciden en la vulnerabilidad social. Se concluye que los padres y madres de familias que se encuentran en situaciones de vulnerabilidad enfrentan diversos obstáculos que les impiden ejercer su parentalidad de manera óptima, ya que las oportunidades juegan un papel primordial para la creación y ejecución de un proyecto de vida familiar.

Palabras clave: vulnerabilidad social; rol parental; familia; contextos de vulnerabilidad.

Introduction

Human beings, throughout history, have faced diverse situations forcing them to adapt to survive (Rodríguez & Quintanilla, 2019; Suárez & Riaño, 2021). However, today individuals do not seek only to survive but rather aspire to well-being and quality of life (Fiorentino, 2008; Córdoba, 2007). This search is limited or affected by the different situations of adversity in contexts that provide factors configuring social vulnerability, which can imply a high risk for the development of the individual, future generations, and families (García et al., 2018; Ranabir, 2014).

The factors that lead to social vulnerability can imply a high risk for the development of the individual in their life in society. These contexts can influence decision processes, behavior, and the construction of personality (Padilla et al., 2014; Andrade, 2009; Islam & Al-Amin, 2019; Chávez-Hernández & Macías-García, 2016). Likewise, these situations that carry risks could affect intra-family relationships, making the dynamics and obligations implicit in the parental role, such as parenting, care processes, attention, socialization, and education of children, become a challenge (Richaud, 2013; Ortiz-Ruiz & Díaz-Grajales, 2018).

In the social sciences, the concept of vulnerability was introduced in the 1980s in studies on social inequality and poverty; an era when assistentialism was common since concern for fellow men gave rise to the need to prioritize individuals who were in conditions requiring aid of some kind to provide them with a better quality of life. In this same way, the ties of cooperation between different nations in pursuit of development were strengthened (Valdés, 2021; Tavares et al., 2018; Guzmán, 2017; Gitz, 2021; Caballero, 2016).

On the other hand, the intense pressures of neoliberalism manage to discourage the struggle of communities against the so-called opportunity structure, with strategies such as fragmentation and blocking the power of ordinary citizens, repression by different means of the right to protest, and the reduction of militancy spaces (Benítez, 2017). The social fabric is directly related to life experiences woven with lifestyles, in terms of food possibilities, medical security, education, culture, and leisure. These individual life paths are linked at some point with other people, in what is known as homogamy: the tendency for people to marry or unite according to their socioeconomic and cultural levels. It can be stated, then, that the exercise of paternity or motherhood is articulated with various structural conditions which are in continuous change.

Valdez (2021) points out that for a long time, the study of realities that negatively affect human beings has been a great concern in societies. The introduction of the concept of social inequality has given an open letter to the understanding of different concepts or categories; like social vulnerability. The existence of this concept became a vital aspect of the construction of instruments such as public policies and community interventions. In this way, many actions with a focus on human well-being were founded and strengthened, which denotes the vitality of this approach for the community (Valdés, 2021; Espina & Muñoz, 2014).

Families that are exposed to adversities placing them in contexts of vulnerability such as domestic violence, drug addiction, deprivation of liberty of a family member, economic precariousness, and poor access to health and education services, face different limitations in their daily lives that are unfavorable for upbringing, education, economic activity that serves as a livelihood, and the formation of healthy emotional ties within the family (Ferreyros, 2007; Varela et al., 2015; Richaud, 2013; Grau & García-Raga, 2017). That is why we must delve into how relationships between parents and children are configured, and what roles fathers and mothers assume from these contexts of vulnerability.

It is inevitable to contemplate the multiple challenges that fathers, mothers, or caregivers face since these roles require competencies that result from experiences lived according to the diversity of the context and its permanent change, forcing in some way to adapt (Richaud, 2013; Varela et al., 2015). The aforementioned gives results in learning acquired through the daily exercise of a parental role, which opens caregivers the door to a world where all their experiences revolve around the development of this role since this is the moment where the responsibilities that come with raising, socializing, and educating fall on them (Franco, 2016; Vargas et al., 2018; Tinoco & Féres, 2012).

The problem identified in this research arises from a process of reading the realities in four scenarios, which are the professional practice centers of each of the researchers contributing to this article. These centers have diverse characteristics, however, all of them involve intervention work with communities. These communities have in common the fact that they are exposed, as well as their families, to factors that make them socially vulnerable, such as the scarcity of resources, social contexts with problems of insecurity, lack of opportunities from the perspectives of the environment or the family’s nature itself, among others.

From this perspective, it is considered important to investigate how social vulnerability affects families and their members in the relationship, as well as in the adaptations, capacities, and abilities that have an impact on the construction, functionality, and permanence of those who exercise a parental role. (Pizarro, 2001; Richaud, 2013). The family is the first construction of interrelation, norms, habits, behaviors, skills, and abilities for life; this provides the learning basis for every relevant aspect of development in society. Having this clarity, it is necessary to take into account the influence exerted by various social factors to reach the limit of modifying already established guidelines, conceptions, or beliefs (Pizarro, 2001; Richaud, 2013).

Parenting skills develop as the role of mother or father is acquired. The exercise of this role generates challenges that are mostly changing due to the transformations that arise from the contexts and the adaptations achieved, seeking to improve the fulfillment of parental functions (Richaud, 2013). The relationships established between fathers, mothers, and children are aspects that take shape according to the needs of children and the life cycle in which they find themselves (Richaud et al., 2013; Tinoco & Féres, 2012).

The main question of this research is based on the need to know, from a comparative perspective, the relationships formed between social vulnerability and the parental role, through the identification and characterization of the types of vulnerability that occur in families. Likewise, the actions that the parental role occupies before various contexts that configure situations of vulnerability are described, and the actions that fathers and mothers who are heads of household take in the face of new realities and the risks that they face. Under these investigative parameters, it is recognized that there are articulations between the lifestyles and experiences of the subjects and the context, understood as constitutive dimensions of social vulnerability. Linked to this context is the development of parental roles, which are established in the historical moment that individuals live and are marked by their biographical stories; this idea overcomes the conception of the parental role as a matter related exclusively to the exercise of being a father or mother and a learning exercise.

Materials and methods

This research had a qualitative, descriptive approach, with which we sought to understand the reality of the parental role within the phenomenon of social vulnerability. Due to the nature of the objective, the study was based on the interpretive-hermeneutic paradigm, the inductive-analytical reasoning method, and the phenomenological research method. The participants corresponded to twelve fathers and/or mothers who were heads of households and identified as people in contexts of social vulnerability. The study contexts were: the La Paz Penitentiary Establishment, the Unbound Foundation, the Secretary of Health and Social Protection of Itagüí’s Mayor’s Office, and the Pueblo de los Ninos Corporation; located in the municipalities of Itagüí and Medellín.

The interview was used as an instrument for collecting information, which allowed us to know the experience of the interviewees concerning the parental role as it related to social vulnerability under different dimensions of analysis. The participants were selected based on the information provided by the organizations since they had the characterization of the families or individuals at risk of vulnerability. To apply the interview, a documentary search on the topic was carried out, which facilitated the understanding and prioritization of key points for the design and application of the technique.

The interviews were structured based on three main categories guided by the specific objectives of the research and related to the analysis of social vulnerability, the parental role, and family functioning. The information collection instrument was previously subjected to pilot testing and peer review by experts. After obtaining the interview texts, the units of analysis were coded to find common elements among the participants within the framework of the social vulnerability-parental role-family functioning triad (Martínez Miguélez, 2017; Strauss & Corbin, 2022). Coding was carried out at three levels through an Excel sheet called the semantic network: open coding, axial coding, and inductive categorization. The data from this network were processed through the ATLAS ti.v22 software, resulting in a total of 492 markings within the hermeneutic unit, which was made up of nearly 40 thousand words —approximately 65 pages.

Ethical aspects of research

In this research, all the necessary ethical aspects and principles were applied to protect participants and the information collected. Since this research contained a qualitative approach, the application of particular criteria was necessary: participants knew the purposes of the research and the role they played within the study (informed consent). In addition, the return of the findings was guaranteed to ensure their dignity and socio-emotional stability, as well as anonymity and adequate treatment of the information.

The design of the data collection technique adhered to the criteria of reliability, authenticity, validity, transferability, applicability, theoretical-epistemological agreement, and neutrality or objectivity. These criteria were the fundamental basis to support the information collected and the interpretations for the requirement to know and recognize the context in which the participants operate and their way of doing so. Likewise, once the instrument was applied, compliance with the relevance criterion was sought, which deals with the evaluation of the proposed achievements based on the objectives (Noreña et al., 2012).

During the research process, verbal and non-verbal language that facilitated the construction of bonds of trust was sought, contributing to interaction with the participants and depth in the narratives collected. Above all, respect, anonymity, human rights, dignity, emotions, and feelings were preserved; and any aspect that might disturb the tranquility of participants. Therefore, the investigative process was carried out with empathy, a sense of humanity, and an understanding of all the events that participants have gone through, their learning, and strategies to seek to develop in a community and societal environment (Mesía, 2007).

Results

The results are presented by inductive categories according to the data’s treatment, which includes the semantic network as its corresponding description and interpretation. The first category is related to how the participants face vulnerability from their assets. The second allows us to describe the parenting and attachment processes, taking into account the people in families with an important role in these dynamics. The third category is articulated with the first two and refers to the rules and principles that structure behavior patterns and the environment in the family. The fourth inductive category describes the opportunity structure of families and parents who find themselves in situations of vulnerability, which is associated with the first findings network and the phenomenon of the parental role. Finally, the fifth category focuses on the interpretation of social vulnerability from the experience of the participating subjects themselves.

In this way, each of these categories focuses on important themes that relate social vulnerability to the parental role and explain part of the feelings of mothers and fathers concerning the exercise of parenting in situations of difficulty. From each of the inductive categories, axial coding and open codes emerge that arise from the unit of analysis, with which it is possible to illustrate five semantic networks that are organized as follows, according to the greatest number of codes associated with their respective conceptualization:

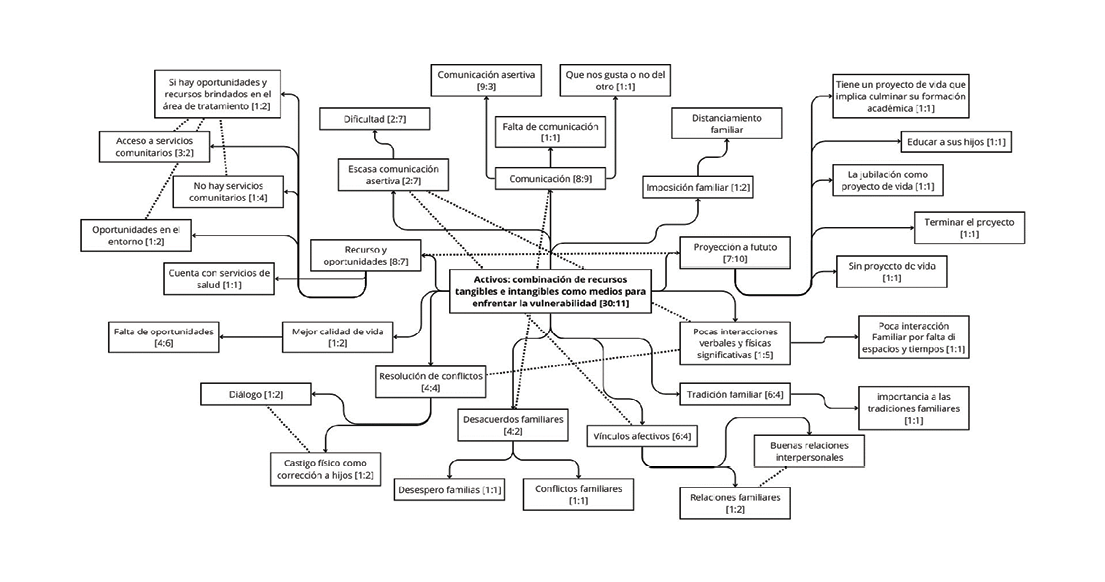

Inductive category “Assets: a combination of tangible and intangible resources as means to address vulnerability.” From the results obtained with the support of the ATLAS ti software, this inductive category is identified, which is illustrated in Figure 1 and which brings together eleven axial codes of which four are related to each other, and twenty-four open codes, of which only one is related to other codes.

Figure 1. Semantic network “Assets: a combination of tangible and intangible resources as means to face vulnerability”

Source: own elaboration

The axial codes “lack of assertive communication,” “despair,” “little family interaction,” “imposition of roles,” “beliefs,” “lack of time and space,” and “disagreements” have a greater density, and are closely related with the lack of opportunities and low economic income, so it is possible to conclude that opportunities play a primary role in the configuration and development of a family life project. In the case of the participants, the opportunities in the environment are scarce and this makes it difficult or limits the projection and materialization of a collective life project. The understanding of the future projection among the participants revolves around the idea of being professional and, from the parental role, families recognize education as a vital and significant pillar. For this reason, they refer to finishing or completing their studies, which for one reason or another could not be developed before, and is now perceived as a possibility of improvement, which is also projected on their children.

The aforementioned allows us to reach one of the most reflective spheres for this research, leading to the question of what happens in the environment and how we can access a better quality of life, which is affected by the lack of opportunities and reduces the possibility of families’ future projection.

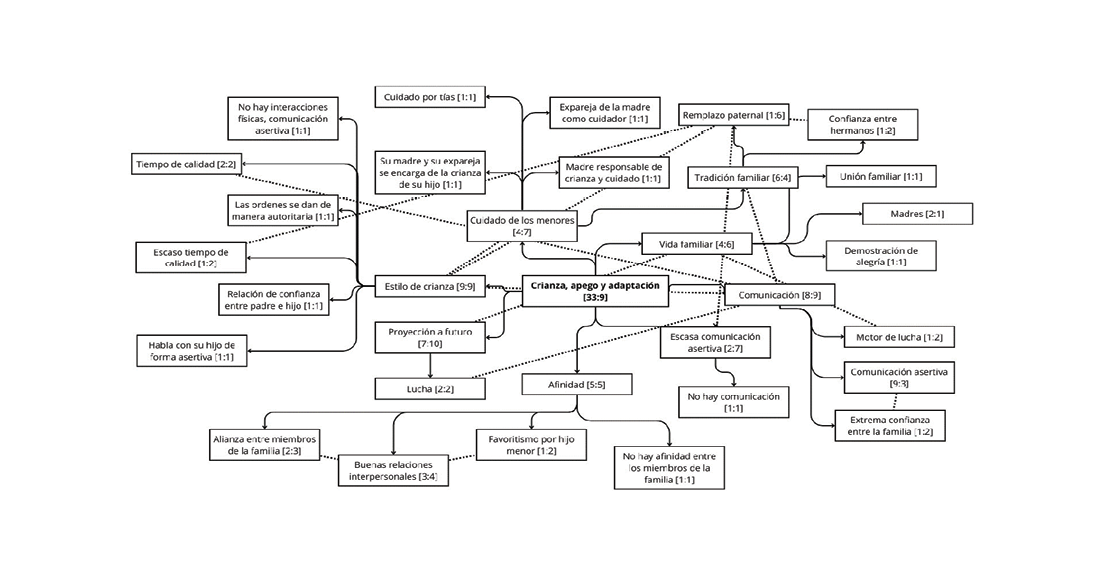

Inductive category “Parenting, attachment and adaptations.” In this semantic network illustrated in Figure 2, nine axial codes and twenty-four open codes are broken down. It becomes evident how the family union is characterized by a common struggle to carry out the family life project. Here mothers play a fundamental role since they are in most cases seen by the other members as pillars of family life; activities that promote not only unity but also the tasks that maintain the functioning of the home take place around them.

Figure 2. Semantic Network “Parenting, attachment and adaptations”

Source: own elaboration

“Care of minors,” being one of the most relevant codes, is articulated with the “parenting style” code; both concerning the “quality time” code. Regarding this, the interviewed subjects state that they have an authoritarian parenting style; however, there is a “parental replacement” on the part of grandparents and older children, who are assigned the functions of caring for the minors and supporting household chores. It highlights the fact that fathers, as the male figure in the home, do not get involved in this type of parenting tasks and functions. This is linked to “family tradition” and communication, whether or not based on assertiveness and trust, which is affected by limited quality family time.

As a result of this semantic network, a different perspective on future projection is found. This is presented as a purpose of permanent struggle over time according to the opportunities and means that are presented to families. Parenting and everything that derives from it is relevant to determine the relationship between vulnerability and parental role; in this case, care is commonly assigned to women. Relationships and communication end up being determining aspects of the integral formation of a human being. Variations or lack in these aspects give rise to parental replacements that become established and gain sufficient strength to generate alliances or favoritism in families.

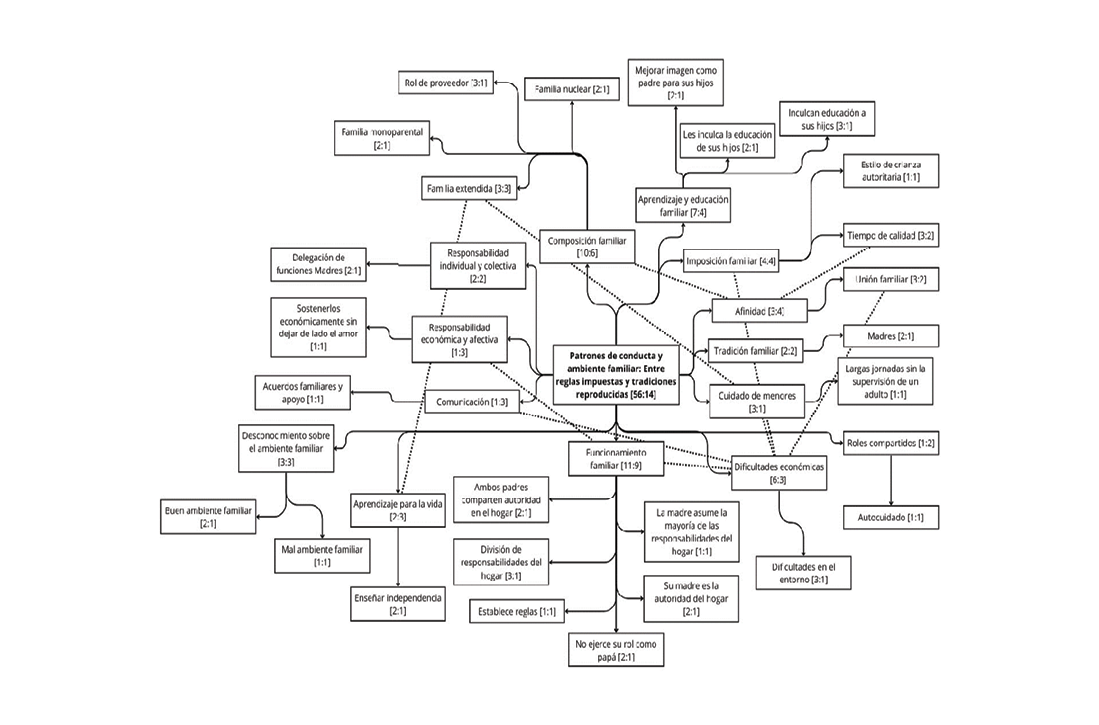

Inductive category “behavior patterns and family environment: between imposed rules and reproduced traditions.” In this semantic network of inductive categorization, twelve axial codes and thirty-three codes are broken down, as seen in Figure 3. Families have a diverse composition and the interviews reflect the great variety in family typology; researchers found single-parent families, extended and nuclear, in which fathers mostly occupy a provider role and are unaware of family functioning, while mothers bear a greater burden as they are involved with economic support, household chores, and parenting.

Figure 3. Semantic Network “Behavior patterns and family environment: between imposed rules and reproduced traditions”

Source: own elaboration

These families report having economic difficulties, a situation that leads several of their members to work long hours to support the household financially. Without a doubt, this affects the family union and the affinity between its members, since the care and attention to minors takes a backseat. Due to this, matters relating to the delegation of functions and family functioning often fall to minors or grandparents. Despite this, fathers and mothers maintain good communication with their children, which results in a good family environment in which roles are shared and allows the establishment of rules that facilitate family unity.

On the other hand, in single-parent families, the lack of a paternal figure stands out, which is why the mother is the one who assumes most of the household chores, as well as the authority. Likewise, family traditions end up focusing on the figure of the mother and the learning that is intended to be passed on to children: discipline, patience, and independence. However, the lack of quality time with the family means that emotional and caring responsibilities take a backseat. This is reflected in codes of greater density and recurrence such as “economic difficulties,” “environmental difficulties,” “care of minors,” “economic and emotional responsibility,” “quality time,” “lack of knowledge about the family environment,” “shared roles,” and “family composition.”

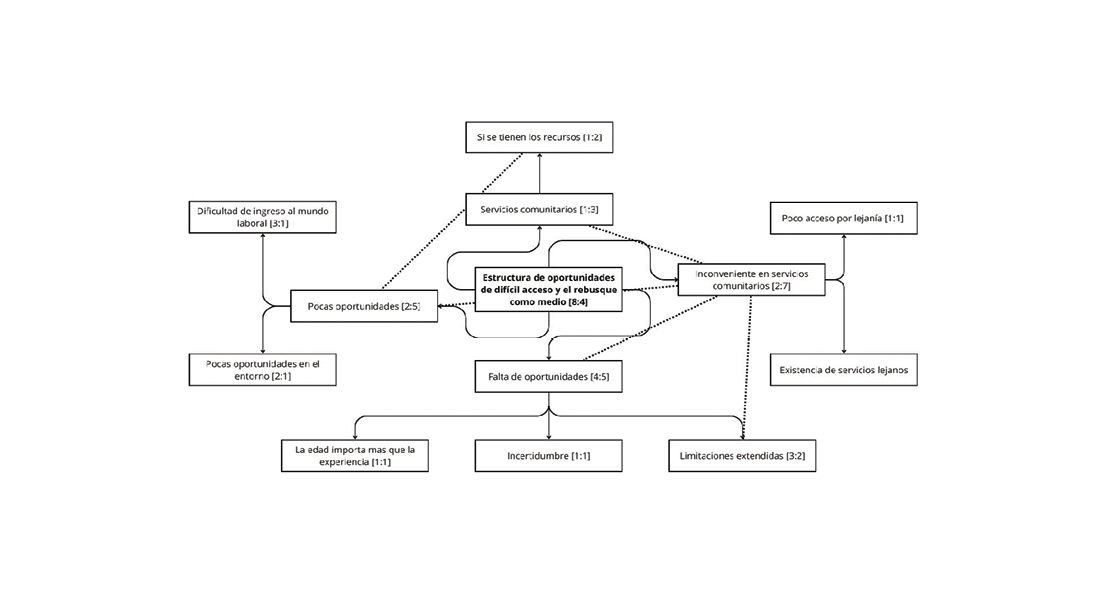

Inductive category “structure of difficult-to-access opportunities and foraging as a means.” From this semantic network, illustrated in Figure 4, 4 axial codes are broken down, of which three are related to each other: 1) community services, 2) inconveniences with community services, and 3) lack of opportunities. In addition, eight open codes were identified, which show different densities at various levels, for example, “inconveniences in community services” is related to the open code “it not only limits me but many people,” which belongs to the axial coding of “lack of opportunities.”

Figure 4. Semantic network “Structure of difficult-to-access opportunities and hustling as a means”

Source: own elaboration

This semantic network allows researchers to have a broader view of the relationships within the answers given by participants. The “lack of opportunities” is the code with the highest density within the semantic network because this is a direct consequence of the “structure of opportunities that are difficult to access and hustling as a means;” furthermore, it is related to “inconvenience in community services” because they are presented as difficult to access for territorial reasons or because they are far from the area where the individuals live.

On the other hand, very specific codes of social vulnerability are seen such as “age is more important than experience,” which refers to the difficulties in finding space in the world of work, and from there, we derive the idea that these factors directly affect the economy, which causes situations of “uncertainty” before the “lack of opportunities” in the environment that foster circumstances of vulnerability. This is reflected in codes of greater density and recurrence such as “lack of opportunities,” “inconveniences in community services,” and “difficult access to the world of work.”

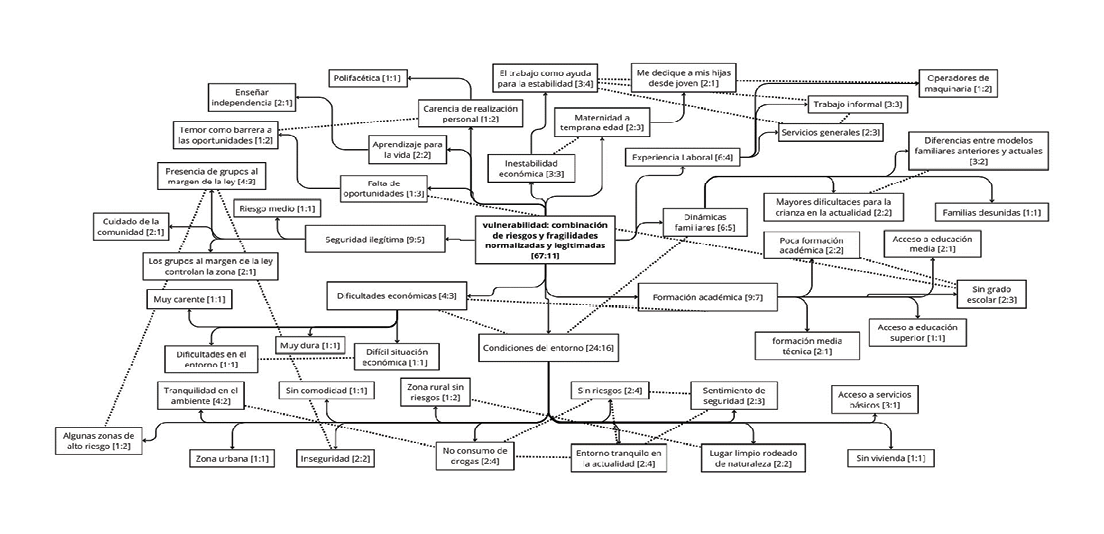

Inductive category “vulnerability: a combination of normalized and legitimized risks and frailties.” From the analysis of the ATLAS ti software, this inductive category emerges with a total of fifteen axial codes and fifty-three open codes, as shown in Figure 5. According to the related codes in the semantic network, it can be seen that for low-income families economic problems manifest a lack of opportunities, which in turn are related to aspects such as early motherhood, illegitimate security in the environment in which they live, and a lack of personal fulfillment on the part of paternal or maternal figures.

The people interviewed declare that the areas where they live, despite being places where they do not see risks and feel safe, turn out to be spaces where security is provided illegitimately, that is, by groups outside the law; according to the participants, these groups are the ones who maintain order and control in these areas, which denotes an absence of the State in matters of security.

Family dynamics are affected, because the participating subjects say they are experiencing difficulties in raising children due to time and economic issues. This is related to difficulties and economic instability, which in turn is associated with the fact that many of the fathers and mothers interviewed have not achieved higher education, so they must dedicate themselves to informal or poorly paid jobs.

Figure 5. Semantic network “Vulnerability: a combination of normalized and legitimized risks and frailties”

Source: own elaboration

In terms of parenting, parents focus mostly on teaching their sons and daughters to be independent; this is associated with the fact that, due to lack of time, the hustle economy, and lack of opportunities, parents are forced to sacrifice most of their time working, which leaves them little space for caring and attending minors. This is reflected in codes of greater density and recurrence such as “economic difficulties,” “environmental conditions,” “care of minors,” “economic and emotional responsibility,” “quality time,” and “family composition.”

Discussion

Social vulnerability includes multiple aspects that can significantly and diversely affect how fathers and mothers exercise their parental role. The economic situation of a family is one of the most relevant factors when exercising the role of caregiver in a family with minors, which causes families to develop strategies to seek family development. The dynamics in households with low economic income are modified in such a way that parents focus mainly on their role as economic providers, so children must develop survival and independence capabilities (Adaro & Muñoz,2014; García, Munévar & Hernández, 2018); this is evident from the responses of the subjects interviewed because they state that they want to teach their children the value of independence and how the children “take care of themselves,” as they have to work long hours to give their families the necessary financial support (Fiorentino, 2008; García, Munévar & Hernández, 2018).

Parenting styles in families in situations of social vulnerability are differentiated by a strong authority figure, generally maternal, since it is mothers who, as evidenced in the interviews, have the greatest burden of responsibilities at home. They are the ones who in most cases take care of cleaning tasks, raising children, and contributing financially to the household (García, Munévar & Hernández, 2018; Ortiz & Díaz, 2018; Toksanbaeva, 2001), in addition to many other functions and roles that depend on the needs of the family in general (da Fontoura et al., 2018; Pintas et al., 2021).

Communication, family dynamics, family roles, and the family environment are significantly influenced by the conditions of the environment in which the family lives, and by the security and opportunities to which members have access (Foster et al. ., 2017; Nobre et al., 2018). Many of the fathers and mothers interviewed did not have access to higher education, so their scope of employment was reduced, and this meant that their income was not optimal to be able to afford the basic needs of their family. This condition forces them to live in places where they are exposed to insecurity or illegitimate security, and where they do not have access to basic or community services, which greatly hinders the families’ ability to project their future and forces parents to leave other paternal responsibilities in the background that are delegated to their children, especially older ones and in some cases to grandparents (Ortiz & Díaz, 2018; García, Munévar & Hernández, 2018).

It is possible to perceive that families that find themselves in this type of vulnerable situation, despite not having the necessary resources and time, look for a way to preserve and reproduce family traditions, maintain their bonds and strong emotional ties, and communicate assertively for the adequate resolution of conflicts at home (Ortiz & Díaz, 2018; García, Munévar & Hernández, 2018; Richaud, 2013). The participants state that they maintain constant and respectful communication with each other, seeking mutual support and spaces to share the quality time that favors family unity.

Conclusions

Family dynamics and configuration are influenced by traditions, composition, functioning, emotional ties, and communication; these factors prove to be essential to achieving family unity and harmony. In this same area, consistent with the implications is the imposition of roles or tasks, family dynamics, and traditions in family construction. All of these dimensions can be affected and limited by the environmental and economic conditions of the family since fathers and mothers of families that are in vulnerable situations face various obstacles that prevent them from optimally exercising their parenting because opportunities play a fundamental role in the configuration and materialization of a family life project.

The conditions of social vulnerability and the exercise of parental roles are directly related. Poverty is already a condition of violence that tests the subjects’ capacities for self-care, even more so when there are others in charge. If in the context of poverty, it can be said that there is stigmatization and criminalization, it is necessary to recognize this as another violation of families and that the result of the exercise of care, concerning the structures of political possibilities, becomes more closed and austere, thus increasing the repetition of the violation. The need for studies focused not on the responsibility of families, but on the policies that exist to fight against poverty conditions, is then evident. In addition to this, at a methodological level it is recommended that, for similar studies, the implementation of complementary techniques such as participant observations, focus groups, and extended interviews with other people who make up the families are considered. This is to carry out triangulation processes that validate the findings found.

Authors’ contribution

Luisa Betancur: Application of instruments (#4) and writing. Data processing with Atlas Ti.

Mariana Arango: Application of instruments (#4) and writing. Data processing with Atlas Ti.

Nagibet Casas: Application of instruments (#4) and writing. Coding and categorization.

Sebastián Velásquez: Application of instruments (#4) and writing. Coding and categorization.

Abad Parada: Analysis and interpretation of results. Coding and categorization. Use of Atlas Ti. Style review.

Alejandra González: Design of the instrument. Analysis and interpretation of results. Disciplinary review. Final style review.

References

Adaro Espina, B.B. & Muñoz Rubio, J.E. (2014). El bienestar psicosocial desde la perspectiva de niños y niñas que viven en contextos de vulnerabilidad social. [Tesis de Grado, Universidad Andrés Bello] http://repositorio.unab.cl/xmlui/handle/ria/1256

Andrade, M.I., & Laporta, P. (2009). La teoría social del riesgo: una primera aproximación a la vulnerabilidad social de los productores agropecuarios del Sudoeste bonaerense ante eventos climáticos adversos. Mundo Agrario, 10(19), 1-20. https://www.mundoagrario.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/v10n19a08

Benítez, J. (2017). Estructura de oportunidades políticas y movimientos sociales urbanos en la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires (2007-2015). Espacialidades, 7(2), 6-33. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/4195/419553524001/html/

Chávez‐Hernández, A. M. & Macías‐García, L. F. (2016). Understanding suicide in socially vulnerable contexts: psychological autopsy in a small town in Mexico. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 46(1), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12166

Córdoba, R.C. (2007). Capacidades y libertad. Una aproximación a la teoría de Amartya Sen. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 65(47), 9-22. https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2007.i47.50

da Fontoura Winters, J.R., Heidemann, I.T.S.B., Maia, A.R.C.R. & Durand, M.K. (2018). Empowerment of women in situations of social vulnerability. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, 4(18), 83-90. https://doi.org/10.12707/RIV18018

Ferreyros Peña, M. (2017). Apego seguro y desarrollo del infante en poblaciones vulnerables. Avances en Psicología 25(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.33539/avpsicol.2017.v25n2.350

Fiorentino, M.T. (2008). La construcción de la resiliencia en el mejoramiento de la calidad de vida y la salud. Suma Psicológica, 15(1), 95-114. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=134212604004

Foster, C. E., Horwitz, A., Thomas, A., Opperman, K., Gipson, P., Burnside, A., Piedra, D.M. y King, C. A. (2017). Connectedness to family, school, peers, and community in socially vulnerable adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 321-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.011

Franco Rueda, A.M. (2016). Fortalecimiento de las competencias que favorecen el desarrollo de estilos de apego seguro y la prevención de prácticas maltratantes o negligentes, en cuidadores primarios de niños y niñas en primera infancia. [Tesis de Grado, Universidad Nacional de Colombia]. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/57834

García Muñoz, C.M., Munévar Quintero, C. A. & Hernández Gómez, N. (2018). Agenciamientos socio-jurídicos en mujeres con jefatura de hogar, en contextos de pobreza y vulnerabilidad social. Civilizar Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 18(35), 73-90. https://doi.org/10.22518/usergioa/jour/ccsh/2018.2/a06

Grau, R. & García-Raga, L. (2017). Learning to live together: a challenge for schools located in contexts of social vulnerability. Journal of Peace Education, 14(2), 137-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2017.1291417

Islam, M. N. & Al-Amin, M. (2019). Life behind leaves: Capability, poverty and social vulnerability of tea garden workers in Bangladesh. Labor History, 60(5), 571-587. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2019.1623868

Martínez Miguélez, M. (2017). Ciencia y arte en la metodología cualitativa. Trillas.

Mesía Maraví, R. (2007). Contexto Ético de la Investigación Social. Investigación Educativa, 11(19), 137-151. https://revistasinvestigacion.unmsm.edu.pe/index.php/educa/article/view/3624

Nobre, G.C., Valentini, N.C., & Nobrea, F.S.S. (2018). Fundamental motor skills, nutritional status, perceived competence, and school performance of Brazilian children in social vulnerability: Gender comparison. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 335-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.007

Noreña, A.L., Alcaraz-Moreno, N., Rojas, J.G. & Rebolledo-Malpica, D. (2012). Aplicabilidad de los criterios de rigor y éticos en la investigación cualitativa. Aquichan, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2012.12.3.5

Ortiz-Ruiz, N. & Díaz-Grajales, C. (2018). Una mirada a la vulnerabilidad social desde las familias. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 80(3), 611-638. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32158229005

Padilla, J.P., Álvarez-Dardet, S.M. & Hidalgo, M.V. (2014). Estrés parental, estrategias de afrontamiento y evaluación del riesgo en madres de familias en riesgo usuarias de los Servicios Sociales. Psychosocial Intervention, 23(1), 25-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.5093/in2014a3

Pintas Marques, C., Rava Zolnikov, T., Machado de Noronha, J., Angulo-Tuesta, A., Bashashi, M. & Nogueira Cruvinel, V. R. (2021). Social vulnerabilities of female waste pickers in Brasília, Brazil. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 76(3), 173-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2020.1787315

Pizarro, R. (2001). La vulnerabilidad social y sus desafíos: una mirada desde América Latina. CEPAL.

Ranabir Singh, S. (2014). The Concept of Social Vulnerability: A Review from Disasters Perspectives. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies, 1(6), 71-82. http://www.ijims.com

Ranci, C., Brandsen, T. & Sabatinelli, S. (Eds.). (2014). Social vulnerability in European cities: The role of local welfare in times of crisis. Springer.

Richaud, M. C. (2013). Contributions to the study and promotion of resilience in socially vulnerable children. American Psychologist, 68(8), 751–758. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034327

Richaud, M. C., Mestre, M. V., Lemos, V., Tur, A., Ghiglione, M. & Samper, P. (2013). La influencia de la cultura en los estilos parentales en contextos de vulnerabilidad social. Avances en Psicología Latinoamérica, 31(2), 419-431. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4459073

Rodríguez, E. & Quintanilla, A.L. (2019). Relación ser humano-naturaleza: Desarrollo, adaptabilidad y posicionamiento hacia la búsqueda de bienestar subjetivo. Avances en Investigación Agropecuaria, 23(3), 7-22. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/837/83762317002/html/

Suárez, V.R. & Riaño Rodríguez, M.P. (2021). El actor se adapta al contexto. [Tesis de Grado, Universidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia]. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12495/7959

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (2002). Bases de la investigación cualitativa. Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Editorial Universidad de Antioquia.

Tinoco Ponciano, E.L. y Féres-Carneiro, T. (2012). Transición para la vida adulta: la transformación del rol parental. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 46(2), 219-228. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/284/28425280003.pdf

Toksanbaeva, M. (2001). The social vulnerability of women. Russian Social Science Review, 42(4), 22-33. https://doi.org/10.2753/RSS1061-1428420422

Varela Londoño, S.P., Chinchilla Salcedo, T. & Murad Gutiérrez, V. (2015). Prácticas de crianza en niños y niñas menores de seis años en Colombia. Zona Próxima, (22), 193-215. https://doi.org/10.14482/zp.22.6129

Vargas-Rubilar, J., Richaud, M.C. & Oros, L.B. (2018). Programa de Promoción de la Parentalidad Positiva en la Escuela: Un Estudio Preliminar en un Contexto de Vulnerabilidad. Pensando Psicología, 14(23), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.16925/pe.v14i23.2265