The deregulation of the salary benefit factors as a competitiveness strategy in Colombia

La desregulación de los factores prestacionales del salario como estrategia de competividad en Colombia

Tipología:

Article of reflection

Fecha de recibido:

November 24, 2017

Fecha de aceptación:

May 21, 2018

Publicado en línea:

julio 19 de 2018

Para citar éste artículo:

Balza-Franco, V. (2018 The Deregulation of the Salary Benefit Factors as a Competitiveness Strategy in Colombia. Clío América, 12(23), p. 87-97. Doi: 10.21676/23897848.2620

ABSTRACT: This article compares salary levels and additional factors to the salary that is paid in some Latin American countries and their relationship with national competitiveness policies. Based on the available data and the author’s judgment, cases of development of deregulation policies of labor laws in force in Colombia are analyzed, as a strategy drawn up by the national government to improve the country’s competitive position. By contrasting variables such as minimum wage, multidimensional poverty index, Gini inequality index and competitiveness index in Latin American countries, with similar indicators from advanced countries in Europe such as Sweden and Germany, and the analysis of their system with regard to the legal wage, it is concluded that there is no apparent correlation between the decrease in the wages of the working class and the increase in the country’s competitiveness.

Keywords: minimum wage - benefit factors - competitiveness - Labor legislation.

RESUMEN: En este artículo se comparan los niveles salariales y los factores adicionales al salario que son pagados en algunos países de América Latina y su relación con las políticas de competitividad nacional. A partir de los datos disponibles y el propio juicio del autor, se analizan casos de desarrollo de políticas de desregulación de las leyes laborales vigentes en Colombia, como una estrategia trazada por el gobierno nacional para mejorar la posición competitiva del país. Mediante el contraste de datos de variables como salario mínimo, índice de pobreza multidimensional, índice de desigualdad de Gini e índice de competitividad en países de América latina, con indicadores similares de países avanzados de Europa como Suecia y Alemania, y el análisis de su sistema legal salarial, se llega a la conclusión de que no existe correlación evidente entre la disminución de los salarios de la clase trabajadora y el aumento de la competitividad del país.

Palabras clave: salario mínimo - factores prestacionales - competitividad - legislación laboral.

JEL: E23, E24

INTRODUCTION

Salary has been the focus of the discussion in labor-management relations, even before unionism was recognized as an activity protected by law, after an arduous political and social process dating back to 1900 (Zorrilla, 1988). It has also been the center of the discussion of public policies of competitiveness in countries around the world. Besides, two significant issues generate conflict between the union sector, the business associations, and the government: the fixing of the so-called “minimum wage” and the regulation of factors additional to the price of labor.

Based on the legacy of Adam Smith, the construction of classical economic theory and nineteenth-century worker-employer relations was based on the employment-wage-birth relationship: employers found a convenient combination of these variables (Altimir, 1979) as exit to “the relationship between the ‘fault of the working class’ and the increasing misery observed” (Aktouf, 2009, p.56). The idea of paying a “sufficient” salary that diminished the demographic explosion of the working class, limiting the number of children a worker could maintain with his salary while avoiding his “eccentric behaviors”: drinking, debauchery, and promiscuity arose. , which resulted in the procreation of more poor people (Aktouf, 2006). The “altruistic” solution was called “salary necessary for the reproduction of the working masses” or minimum living wage, in countries not yet deregulated labor (Aktouf, 2006). Hence, a classic concept of management was derived: it is useless to pay higher salaries to try to obtain a better performance of the employees because granting material incentives to the worker would produce a fast curve of diminishing performance returns (Aktouf, 2006).

In America, throughout the twentieth century, union struggles to obtain better working conditions and guarantees -not exempt from vices of bureaucratization, ideologization, and politicization (Zorrilla, 1988) promoted the development of various labor laws in each country. The regulation of work granted association rights, fixed hours, remuneration of extra work, recognition of breaks and paid vacations, after tortuous worker-employer-government negotiation processes. These labor rights are privileges granted discretionally by the States to their citizens, through their respective legal systems (Archila, 2011).

The discussion presented here focuses on (i) whether there is a correlation between the minimum wage level and national competitiveness and (ii) if there is a correlation between the deregulation of extra factors to salary and the level of foreign investment, the decrease in unemployment and the increase in competitiveness.

METHODOLOGY

Variables used: it was analyzed the variable national competitiveness and its relationship with independent variables such as minimum wage and level of additional factors to salary cost. Unit of analysis: it was analyzed the specific case of the public policy of wage deregulation traced by the government of Colombia in the last ten years. Method: the data on competitiveness variables at the Latin American level, measured with the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) and the amount of foreign direct investment (FDI), were compared with the minimum wage and benefit factor levels of the salary in this group of countries. The competitiveness data of the Colombian case were contrasted with the evolution of the country’s poverty and inequality indexes in the global context. In turn, these data were contrasted with the same indicators in economically and socially advanced countries in Europe. Scope and limitations: conclusions were raised in general and for the Colombian case on the relationship between salaries and competitiveness, as a result of the critical analysis of this information.

RESULTS

Poverty, Minimum Wage and Competitiveness in Colombia

The current conditions of the Colombian working class are similar to those of the English workers of the early twentieth century: an uneducated workforce, with a marked tendency to waste wages in alcohol and other vices (Archila, 2011), generates a vicious spiral of poverty (Balza-Franco, 2013). According to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE by its acronym in Spanish), in 2018 Colombia has about 50 million inhabitants, of which 8 % are in extreme poverty.

A determining factor of the poverty threshold is the low purchasing power offered by the wage earned by the working class, which generates greater poverty and inequality. However, the neoliberal doctrine that has guided the Colombian economic policy of the last 30 years preaches that wages should not increase above inflation. Even high-ranking government officials call the current minimum wage in Colombia “ridiculously high.” The dreaded consequence of a more significant increase in the minimum wage is the increase in the unemployment rate, the great global concern in the last decade.

A report prepared by the International Labor Organization (ILO) for the United Nations (UN) warns that:

Labor and social prospects in the world indicate that the number of unemployed will increase again this year and will go from 197 million in 2015 to 199 million in 2016. [...] It also foresees another increase in 2017 and estimates that 1.1 million people they will be added that year to the ranks of those who do not have a job (UN, 2016, p.1).

More than 200 million unemployed in the world justifies the genuine interest of governments to combat unemployment and inflation, economic variables that can ruin a country. However, these variables are also used as arguments to manipulate the social pressure towards the progressive reduction of real wages, by inducing a sophism: the high cost of salary drives away investment and the generation of employment. This generates an economic dilemma: to reduce the cost of the salary factor to try to attract foreign investment (fleeting perhaps) and increase competitiveness while reducing the purchasing power of the population and discouraging the economy.

The dominant theory of national competitiveness derives from the model of “the competitive advantage of nations” by Porter (1991); from here, the most accepted theoretical models of measurement emerge (Benzaque, Del Carpio, Zegarra and Valdivia, 2010). According to these models, national competitiveness is related, among other factors, to the ability to increase the living standards of the inhabitants and to insert themselves in international markets. One of the indicators of national competitiveness that emerges here is the Global Competitiveness Index (IGC), which measures “the ability of a nation to achieve sustained economic growth in the long term concerning the resources available” (National System of Competitiveness, Science, Technology, and Innovation, 2017). Table 1 shows data on the IGC score, position in the world ranking and the minimum wage of the countries of Latin America (LA) in 2017.

Minimum wage and IGC index in Latin America (Year 2017).

Judging from the available data, the inverse relationship that arises between competitiveness and wages is sophistic. The highest minimum wage in LA is paid in Argentina and the lowest in Nicaragua. In turn, Chile (4th highest minimum wage) leads the group of most competitive countries in the region according to the IGC index, while Paraguay shows the worst performance. Panama pays the highest salary in the region and occupies the third position in competitiveness in this group of countries. Under the premise that at a lower price of the salary factor, the higher the level of competitiveness, Nicaragua would be the most competitive country in Latin America. The data do not allow establishing statistically significant parameters, but there is no correlation between low salaries and high competitiveness.

Labor Rights, Salary Benefit Factors, and Foreign Direct Investment

The dominant neoliberal economic policy in Latin America perceives the labor rights associated with the compensation of extra or night work as a competitive disadvantage to draw the desired foreign investment; This conditions the generation of jobs at ever lower wage rates. By deregulating these surcharges, we seek to make the business environment “more competitive” and attractive.

A case that illustrates this strategy in Colombia dates from the 2002-2010 government. The executive, through the Ministry of Foreign Trade, designed labor deregulation strategies to “sell” the country as an investment destination:

Proexport presented the [...] results of the study and stated that, according to the balance sheets obtained, ‘Colombia has a highly competitive labor regime from the employer and is well positioned concerning the region. (...) The analyzes indicate that ‘the range of hours of the daytime working day, contemplated in the Colombian legislation is the third most extensive together with Peru being only surpassed by the Chilean and Brazilian.’ The country also has the broadest range of hours of the working day, sharing the first place with Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru and Argentina (Colombian Federation of Human Resources ACRIP, 2009, p.1).

The strategy materialized by reducing the time slot legally considered “extra night work”: in this period, the Colombian government carried out a “re-engineering” of the labor regime in force until then, attacking the distinction between day and night work, in order to reduce the surcharge for night work (35 %), which was recognized after six in the evening, establishing that the night work began at ten o’clock at night. This change in legislation favored the interests of transnational corporations in large stores: the new standard allowed for extending the service hours to customers until 11 o’clock at night, without having to pay nightly surcharges. The “competitive” strategy of the Colombian government was to turn night into day, for the same salary. It was argued that this would generate more jobs, but, in fact, the effect was to reduce the wage cost of night work to large companies, affecting the primary income of families.

The single extension of the day shift saved annual nightly surcharges for 1440 person-hours for employers, to the detriment of workers. Using the current minimum wage in Colombia as a reference, this amounts to $COP 1 642 200 worker/year. The 2.2 million night workers stopped receiving the not insignificant sum of 3.6 billion COP some 1.2 billion dollars that were capitalized by private companies.

The workers who saw their income reduced were those of the formal sector, regulated by labor legislation, and mainly those of commerce, surveillance, hotels, bars and restaurants, transport, hospitals, and the industrial sector. Some 2.2 million people who work after six in the afternoon, and 1.9 million who do it on Sundays and holidays, suffered a reduction of their monthly salary by 17.2 %, only by the suppression of 35 % of the night surcharge between six and ten at night; and in 5.8 % due to the 25 % decrease in the payment on Sunday and holidays (Vasquez, 2016, p.1).

The measure was partially revised during the 2014-2018 legislation, overcoming multiple political obstacles; finally, it was approved to pay a night surcharge from nine o’clock at night. In the large-scale, labor-intensive trade, labor cost savings were significant.

On the other hand, salary factors, such as bonuses and vacations, constituted an essential weight of the total labor cost to the employer in LA. Certain benefits enshrined in Colombian or Argentine law are unknown in other countries of the continent. For example, the “salary bonus” in Colombia -payment of an additional month of salary to the workers, equivalent to the “aguinaldo” in Argentine legislation (Wageindicator, 2018), is a concept unknown in the United States.

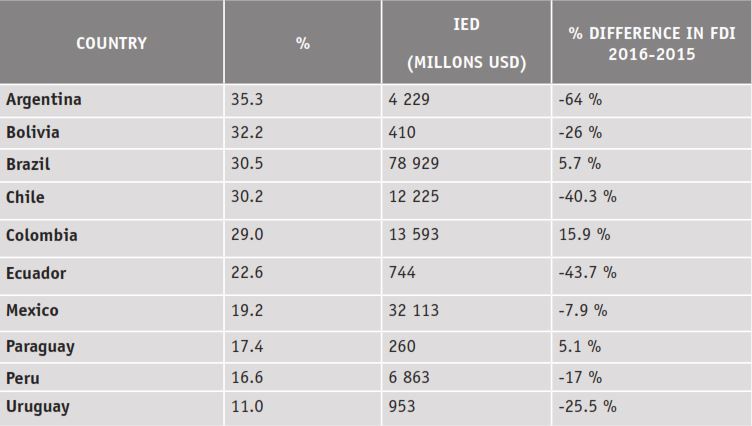

In the same way, in Argentina, the benefit factor is equivalent to more than 35 % in addition to the nominal salary (Urien, 2017). Table 2 summarizes these salary factors (not including payroll taxes) in some Latin American countries and the amounts received from foreign direct investment (FDI) in millions of dollars in 2016 (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, CEPAL by its acronym in Spanish 2017).

Additional salary factors to the payroll (2017).

The reduction of FDI in Latin America was general in the 2015-2016 period; however, there is no evidence of a correlation between the percentage of the additional benefit factor to the salary and the amount of the investment or the increase/reduction in said investment.

Despite having the highest wage costs in the continent, Argentina has experienced policies of strong wage deregulation:

Thus, throughout the nineties, the rules on salary determination were established (salary indexation was eliminated, collective bargaining was decentralized, and wage variations were linked to the evolution of productivity). The right to strike is limited; the vacation regime is altered; the accident prevention system is privatized; various forms of temporary contracts that reduce the cost for employers are put into effect (Ibagón, 2014, p.5).

However, this deregulation has not led to an increase in FDI, as evidenced in Table 2. In contrast, Uruguay, which has the lowest cost of salary surcharge, also presented a reduction in FDI. It is evident that there is no inverse correlation between these factors.

The Salary Factors of the Colombian Wage

In the Colombian case, the “compensations” factors include surcharges to the payroll for social security and social benefits, plus the so-called “parafiscal contributions” payroll taxes destined to finance state entities such as the National Service of Learning (SENA) and the Colombian Family Welfare Institute (ICBF by its acronym in Spanish). This set of surcharges equals an additional 53 % of the nominal salary paid by the employer. These factors strongly impact the cost structure of labor-intensive firms, such as commerce and industry. However, the impact is more significant in small entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs, hindering the sustainability of new companies and stimulating labor informality.

Tax strategies to encourage job creation, aimed at reducing labor costs, have been misguided. The tax reform (Law 1607) of 2012 exonerated Colombian companies from the payment of parafiscal, to create more jobs and to achieve a better distribution of income; but the real effect was to transfer the labor cost to taxpayers: “In practice [...] companies stop paying 13.5 % of parafiscal contributions that end up being charged in large part to natural persons for whom the tax burden increases directly “(Farné and Rodríguez, 2013, p.127). Large companies capitalize or drain the savings generated by this concept via profits, without being translated into new jobs.

DISCUSSION

The Labor Deregulation Strategy and its Effect on National Competitiveness

The “recipes” of the International Monetary Fund, guided by neoliberal policies, advise dismantling the social benefits recognized by law, pointing them out as “competitive disadvantage”, which, if corrected -placing the salary-, would generate more employment (Aktouf, 2009); that is, more people working, but with less income. This theory seems logical, but nothing guarantees that the surpluses of operating profit generated by reducing the wage factor will be translated into new jobs, as was observed in Colombia with the exoneration of parafiscal payments to large companies. A sophism is thus configured: the level of employment is a function inversely proportional to the cost of salary. However, the Keynesian current of economic thought suggests that a better redistribution of income generates economic growth, and therefore a higher level of employment. Keynes proposed “redistributing part of the income of the rich among the poor because an increase in consumption increased production and boosted economic growth” (Delgado, 2014, p.366). That is to say, the higher incomes of the population better wages would generate greater demand for goods and services, achieving higher sales and profits for all companies; this premise is the basis of the European “Welfare State” model, as criticized by Keynes himself as by the neo-liberal economists.

In contrast, the Colombian neoliberal government supports its competitiveness model in a policy of precariousness of work and progressive pauperization of the working class, achieving at the same time meager results of competitiveness at international scales: Colombia ranks 66th out of 133 economies in the world. The ranking published by the World Economic Forum -FEM-; in contrast, it ranks 37th out of 183 countries on the Doing business scalepromoted by the World Bank (Vasquez, 2011). This scale classifies countries that offer a better environment for doing business and hiring staff, given factors such as the favorable nature of the salary and hiring regime: “Colombia is now considered to be ‘the most competitive country in the labor regime’, after labor reforms made outside the social dialogue and against the opinion of the unions “(Vasquez, 2011, p.42).

In addition to the extension of the working day, such reforms include the flexibility of the hiring regime, another potent threat to job stability. The consulting firm Ernst & Young, in partnership with Proexport, published a study on labor competitiveness, comparing the labor laws of Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Peru, Brazil, and Costa Rica; Colombia stood out as the most competitive in the region, considering various labor variables. The study mentioned above was carried out in order to:

... determine the aspects of the regulations that are most attractive for an investor at the time of establishing their business in each of the previous countries’, and included the analysis of the hiring, salary and social benefits schemes, the working day and that of compensation and collective rights (Vasquez, 2011, p.42).

The strategy of promoting the country as an investment destination, tied to a submissive wage policy with significant capital, undermines the rights of workers and the quality of life of the population. However, a correlation between wage reduction and increased competitiveness is not evident, as suggested by using biased indexes such as Doing Business. This indicator, subjective of the business climate, is leveraged in legal re-engineering and is opposed to more complete indicators such as the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) of the World Economic Forum:

The competitiveness index of the World Economic Forum is not based on strategies to reduce labor costs and the precariousness of hiring workers and their working conditions. They are built on the efficiency of institutions, the quality, and efficiency of infrastructure; the soundness of the macroeconomic context; the size of the domestic market; health and primary education; the extension and quality of higher education; the efficiency of the markets; the sophistication of the financial and business markets; the technological availability and innovation (Vasquez, 2011, page 48).

The Cost of the Strategy: the Effect of Wage Reforms on Social Inequality

The GCI shares some variables with the Human Development Index -HDI- as a level of schooling and years of schooling. Strategies designed to strengthen these factors have a lasting impact on a country’s competitiveness -in particular investment in education, as South Korea and Japan have shown-, having an impact on the improvement of living conditions. The deregulation of the wage and benefit system has marginal and temporary effects, without taking into account the high human and social cost. These reforms have generated one of the unequal societies in the world. According to the Gini Inequality Coefficient, by 2010 (World Bank, 2018) Colombia ranked first in world inequality Table 3, with very high levels of poverty (50 % of the population below the poverty line and 17 % in indigence), supported by a working population whose average income only covers 56 % of the poverty line (News Center ONU, 2017).

Gini Inequality Coefficient.

While Multidimensional Poverty in Colombia decreased from 30.4 % to 17.8 % between 2010 and 2016 (DANE, 2017), the country showed poor results in the effort to reduce social inequality. Between 2014 and 2016 the national Gini coefficient was reduced from 52.2 to 51.7 (DANE, 2017), equaling social inequality in Swaziland, one of the poorest countries in Africa.

It is a serious global problem: the current economy has generated massive inequalities; some people are now as rich as entire countries (Piketty, 2014). Social inequality cannot be dismissed as a pro-socialist ideological discourse, it is a concrete and real problem that threatens to become a time bomb for the global society: “Can we imagine a 21st century in which capitalism will transcend towards a way more peaceful and more lasting, or should it simply wait for the next crisis or the next war this time truly global -? “(Piketty, 2014, p.330). Pikketty, Aktouf, and other influential scholars have been emphatic in pointing out that a new way of making capitalism is required.

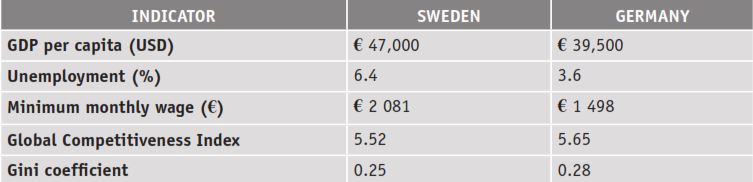

The Third Way: Unconventional Economic, Salary and Fiscal Models

In contrast, the leading countries of the WEF competitiveness index are precisely those that, adopting models of industrial capitalism, show better income distribution, greater institutionality, lower corruption indexes, and better public governance. Given the previous discussion about the inverse relationship between minimum wage and competitiveness, it is appropriate to observe that the data of countries with economic models of a social-democratic nature and with a strong union tradition such as Germany and Sweden (Aktouf, 2009) show precisely the opposite. In fact, regarding wage policy, there is no formal minimum wage in these countries. The high rate of unionization and coverage of collective bargaining more than 87 % of the employed population in Sweden versus 2 % in Colombia make it unnecessary (Vasquez, 2011). In Sweden, there is a compulsory agreement with trade unions in an annual national salary conference between employees and employers (Aktouf, 2009). However, unemployment levels in Germany and Sweden are the lowest in Europe (table 4), their economies are the strongest in the Eurozone and their inflation rates remain low, keeping interest rates stable: the bank German central bank kept the active interest rate below 3 % per annum in the last 6 years (Tradingeconomics, 2018). Recently, the German government issued public debt with negative interest rates (Expansión, 2015).

The successful management models of Swedish and German companies (IKEA, Volvo, Saab, Ericsson, BMW, Volkswagen, Siemens, SAP, Allianz, etc.) and the high level of Swedish technological entrepreneurship (Spotify, LinkedIn, and Skype) are a reflection of their respective economic models. The same happens with legendary Japanese management models based on quality. However, Japanese-style management, German-style or Scandinavian style have no similar universal acceptance than American-style management, being considered “particularities” by the dominant Anglo-Saxon literature with the “impossibility of being transferred to other stages of the world” (Garcia, 2011, p 158).

From the fiscal point of view, in Sweden, the income tax is progressive on income and paid without exception by workers and employers. In contrast, the neoliberal governments do not cease in their efforts to exonerate from paying taxes to the richest in Colombia the income tax will be reduced to companies from 33 % to 28 %, while it will be increased to natural persons. The Swedish State is highly taxed on income-average of 38 % which does not prevent the prosperity of free enterprise; on the contrary, it generates more significant benefits for all citizens, whether they are entrepreneurs or workers. Both Sweden and Germany are intensely capitalist economies, but not of the financial capitalism type-language in the profitability of the banking sectors, but of industrial and technological capitalism. In Colombia, 6 of the ten first companies in the country are banks and only one is industrial.

Economies of Sweden and Germany (2017).

CONCLUSION

The data analyzed show that the premise is that the higher wages of the population, higher unemployment, higher inflation, lower foreign investment and lower competitiveness of the country; the German-Scandinavian example demolishes this economic myth. Despite the unfairness of the comparison between European countries and Colombia 1000 years of historical, cultural, economic and social development separate us the German and Scandinavian economies distribute wealth better and promote a more concerted worker-employer relationship and of mutual respect. Industrial capitalism in Germany and Scandinavia shows that a better wage level of the population drives the economy, increases the level of formal employment and reduces social inequality. The public policy of national competitiveness based on the pauperization of the wage of the working class is wrong; It relates perception of ease of doing business with cheap labor rates. This only increases the social inequality gap, as evidenced by the Gini coefficient. Improving other indicators such as the GCI or the HDI can increase competitiveness.

Given this evidence, it is worthwhile to explore traditional ways-State policies, not government ones to guide the country’s competitiveness, wage policy and the government-business-society relationship in a concerted effort to defeat poverty, inequality, and unemployment as the main obstacles to the progress and prosperity of the nation. Strategies aimed at reducing the cost of salary -e. g. via parafiscal tax reduction to generate new employment should focus on SMEs or new ventures, without allowing large companies to access these tax benefits without real compensation in new jobs.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

Aktouf, O. (2006). Mundialización, economía y las organizaciones: la estrategia del avestruz racional. Cali: Coed: Universidad del Valle, Universidad Libre y Artes Gráficas del Valle.

Aktouf, O. (2009). La globalización, el neoliberalismo y la Administración. En La Administración: Entre tradición y renovación. Cali: Coedición Universidad del Valle, Universidad Libre y Artes Gráficas del Valle.

Altimir, O. (1979). La dimensión de la pobreza en América Latina. CEPAL. Santiago de Chile: NACIONES UNIDAS.

Archila, M. (2011). Cultura e Identidad Obrera. Colombia 1910-1945. (U. Nacional, Ed.) Bogotá, Colombia: CINEP.

Balza, V. (2013). La espiral viciosa de la pobreza. Clío América, 7(14), 170-176. Recuperado de http://revistas.unimagdalena.edu.co/index.php/clioamerica/article/view/761/723

Banco Mundial. (2018). Indice de Gini. New York, EU: Bancomundial.org. Recuperado de https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/SI.POV.GINI?type=shaded&view=map&year=2015

Benzaquen, J., Carpio, L.A.D, Zegarra, L.A. & Valdivia, C.A. (2010). Un índice Regional de Competitividad para un país. Revista Cepal. 102. 69-86.

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe – CEPAL. (2017). La Inversión Extranjera Directa en América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago de Chile: Naciones Unidas (LC/PUB.2017/18-P). Recuperado de https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/42023-la-inversion-extranjeradirecta-%20america-latina-caribe-2017

Delgado, M.J. (2014). J.M. Keynes: crecimiento económico y distribución del ingreso. Revista de economía institucional, 16(30), 365-370. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rei/v16n30/%20v16n30a19.pdf

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. (2017). Pobreza Monetaria y Multidimensional en Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia: Dane.gov.co. Recuperado de http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/pobreza-y-condiciones-de-vida/%20pobreza-y-desigualdad/pobreza-monetaria-y-multidimensional-en-colombia-2016

Escuela Nacional Sindical. (2014). Salario mínimo, salario medio y trabajadores no sindicalizados en Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia: Desde abajo.info. Recuperado de https://www.desdeabajo.info/%20colombia/item/25437-salario-minimo-salario-medioy-trabajadores-no-sindicalizados-en-colombia.html

Expansión. (2015). Alemania coloca también bonos a 5 años con tasas negativas de interés. Madrid, España: Expansion.com. Recuperado de http://www.expansion.com/2015/02/25/mercados/1424867654.html

Expansión. (2018). PIB de Alemania-Producto Interior Bruto. Madrid, España: Expansion.com. Recuperado de: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/pib/alemania?anio=2017

Farné, S. & Rodríguez, D. A. (2013). Empleo e impuestos a la nómina en Colombia. Un análisis de los efectos ocupacionales de la Ley 1607 de 2012 de Reforma Tributaria. (U. E. Colombia, Ed.) Revista de Derecho Fiscal (7), 117-133.

Federación Colombiana de Gestión Humana. (2009). Estudio de Competitividad Laboral Internacional/Proexport. Régimen Laboral Colombiano, un terreno propicio para la empresa extranjera. Bogotá, Colombia: Gestionhumana.com. Recuperado de: http://www.gestionhumana.com/gh4/BancoConocimiento/A/acripcompetitividadlaboral/acripcompetitividadlaboral.asp

Financial Red México. (2017). Salario Mínimo en Latinoamérica ¿en dónde se gana más? México D.F, México: Financial Red México. Recuperado de http://salariominimo.com.mx/comparativa-salario-minimo-latinoamerica/

García, O. (2011). Una aproximación a la gerencia del siglo XXI. Cuadernos de Administración, 27(45), 153-172. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S0120-46452011000100010&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es

Ibagón, N. (2014). Empleo y salarios en Argentina en el periodo de la post-convertibilidad. Clío América, 8(16), 185 - 194. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.21676/23897848.1352

Organización de las Naciones Unidas. (2012). Situación y perspectivas de la economía mundial 2012. Sumario Ejecutivo. Nueva York. ONU. Recuperado de: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2012wesp_es_sp.pdf

Organización de las Naciones Unidas. (2016). OIT prevé un aumento del desempleo mundial en 2016 y 2017. New York, EU: ONU. Recuperado de https://news.un.org/es/story/2016/01/1349001#.WeJ6YGhL_IU

Porter, M. E. (1991). La ventaja competitiva de las naciones (Vol. 1025). Buenos Aires: Vergara.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-first Century. (A. Goldhammer, Trad.) Cambridge-Londres: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Sistema Nacional de Competitividad, Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación. (2018). Índice de Competitividad Global. Bogotá, Colombia: SNCCTI. Recuperado de: http://www.colombiacompetitiva.gov.co/sncei/Paginas/indicadores-internacionales-igc.aspx.

Tradingeconomics. (2018). Alemania-Tasa bancaria activa. New York, EU: IECONOMICS INC. Recuperado de https://es.tradingeconomics.com/germany/bank-lending-rate

Urien, P. (2017). Los costos laborales de la Argentina son los mas altos de la región. Buenos Aires, Argentina: La Nación. Recuperado de https://www.lanacion.com.ar/1974055-los-costos-laborales-de-la-argentinason-los-mas-altos-de-la-region

Vasquez, H. (2011). Colombia, el país más competitivo de la región en Régimen Laboral. Cultura y Trabajo, (82), 42-48. Recuperado de http://www.ens.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/CT_82.pdf

Vasquez, H. (2016). Restituir los trabajadores recargos nocturnos dominicales justo y razonable. Bogotá,Colombia: Escuela Nacional Sindical. Recuperado de: http://ail.ens.org.co/opinion/restituir-los-trabajadores-recargos-nocturnos-dominicales-justo-razonable/

Wageindicator. (2018). El Sueldo Anual Complementario (SAC) o Aguinaldo. Buenos Aires, Argentina: El salario. com.ar. Recuperado de https://elsalario.com.ar/main/Salario/entendetusalario/aguinaldo

World Economic Forum. (2018). Global Competitiveness Index. New York, EU: The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018. Recuperado de: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2017-2018/05FullReport/TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2017%E2%80%932018.pdf

Zorrilla, R. H. (1988). Origen y desarrollo del sindicalismo. Libertas (8), 5-6. Recuperado de http://www.eseade.edu.ar/files/Libertas/43_6_Zorrilla.pdf